Process mapping starts with choosing a process, identifying process goals and choosing a good process name. Tasks and events add the next levels of detail in a process mapping session. This article describes how to identify and organise business process events.

This article follows on from the previous sections of this process mapping tutorial:

Previous steps in process mapping

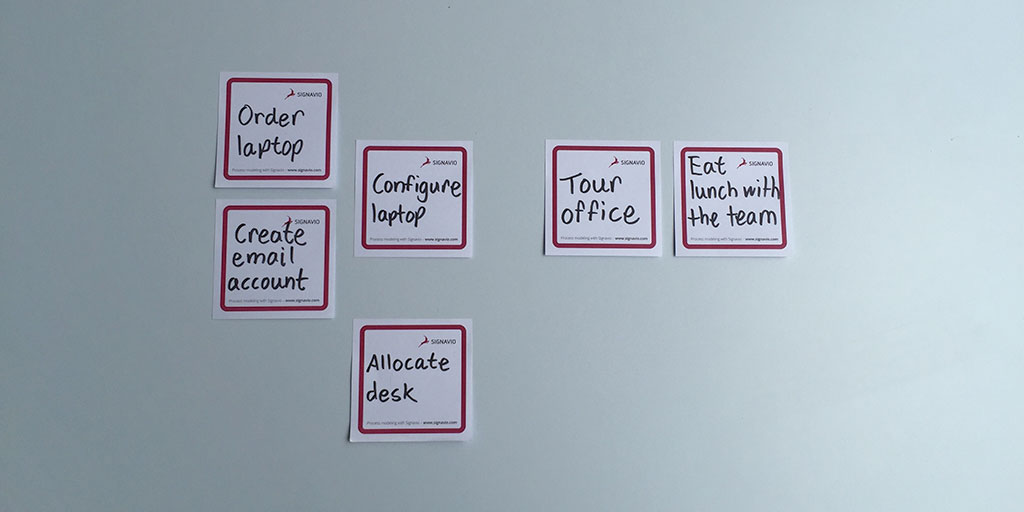

This tutorial started with a process goal. The second part, using the example of an employee onboarding process, continued by creating a timeline of tasks that represent the work on the process.

You can use this kind of tasks timeline as a framework to add business process events to.

Business process events

Business process tasks describe the work in a process. First, you work out what order they happen in, and which tasks you can perform in parallel. Then you can address the following questions about each task.

- What do I need before I can start working on this task?

- How do I know when I can start working on this task?

- How do I know when someone else has completed the task?

- What is the result of completing this task?

- What are the implications of completing this task?

The answers to these questions do not belong inside the task. Instead, events between the tasks answer these questions. These events describe both the reasons for the tasks and their consequences.

In the context of process mapping, a business event describes a noticeable change in either a business process or the context it occurs in. An event is an occasion, such as lunchtime or a delivery arriving somewhere, or a result, such as a management decision.

Identifying process events

The employee onboarding example includes two events that you could have identified before thinking about tasks.

- A new hire signs an employment contract, which starts the onboarding process and marks the end of a successful recruitment process.

- The new hire arrives at the office for the first day at work.

These process milestones are independent of tasks in the onboarding process. In general, a process has a number of key milestones that correspond to events. For the onboarding example, you can skip the end event if you haven’t yet decided what marks the end of the process.

You can look for business process events in several places.

- Start and end events that describe when the process starts and finishes.

- Other natural process milestones that are independent of individual tasks.

- Non-obvious results of previously-identified process tasks.

- Requirements for process tasks that aren’t already covered by an event.

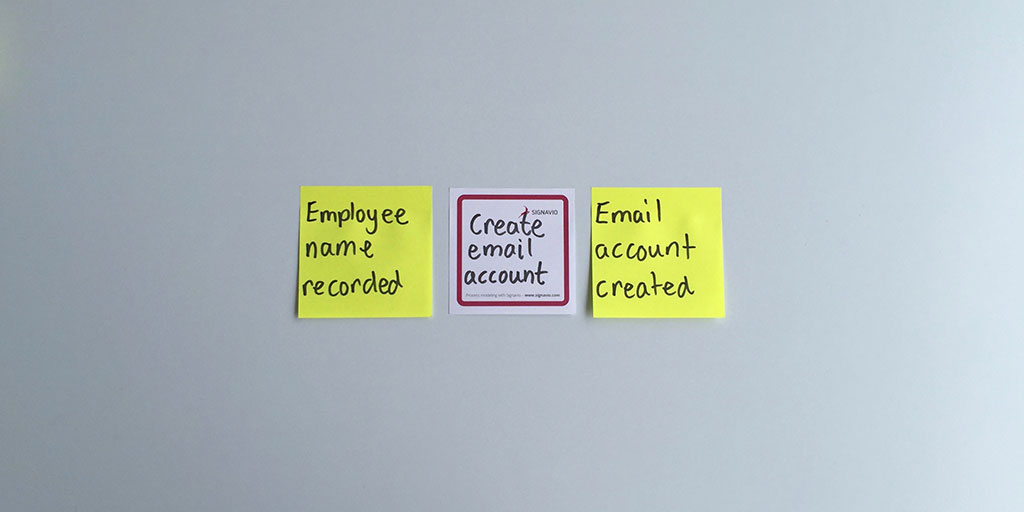

If you look for events that relate to a task like ‘Create email account’, you might end up with requirement and result events like ‘Employee name recorded’ and ‘Email account created’.

These events don’t add much to your understanding of the process. If the process starts with a signed employment contract, which includes the employee’s name, then ‘Employee name recorded’ already happened. Similarly, the successful result of creating an email account is obviously ‘Email account created’, so the event doesn’t add anything to the process model.

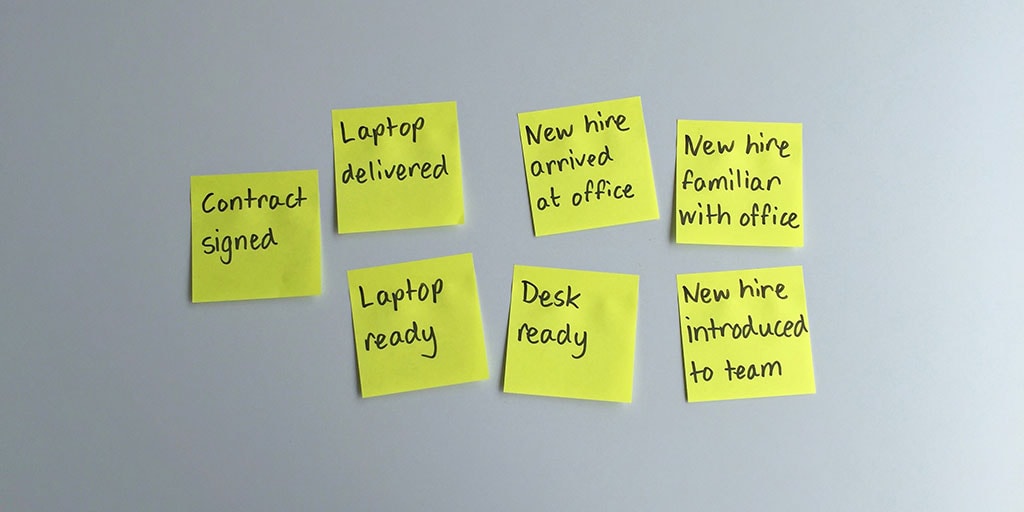

Excluding obvious events, the tasks in the onboarding process example suggest some more events.

- ‘Order laptop’ eventually results in the laptop being delivered, which you have to wait for before you can ‘Configure laptop’.

- The multiple laptop tasks form a group of tasks that result in the laptop being ready.

- After touring the office, the new new hire knows about important locations - fire exits and coffee machines, and generally where things are.

- It makes the most sense to ‘Eat lunch with the team’ at lunchtime.

- Although lunch results in less hunger, having introduced the new hire to the team is more relevant for an onboarding process.

Next, before you can add these to the timeline, you need to come up with good names that fit on sticky notes.

Naming events

Good naming is good communication, for events as much as for tasks. For the onboarding example, a consistent set of event names for the onboarding process looks like this: Contract signed, Laptop delivered, Laptop ready, Desk ready, New hire arrived at office, New hire familiar with office, New hire introduced to team.

Good event names describe some kind of change, so the naming guidelines differ from those for processes and tasks.

- Describe something that happened.

- Start with the name of whatever resource or piece of information changed.

- Use an adjective such as ‘ready’ or a past participle such as ‘signed’ to describe the result of the change.

- Use two or three words, when possible, to keep it short.

Having named the events, you can now add them to the tasks timeline.

Adding events to the tasks timeline

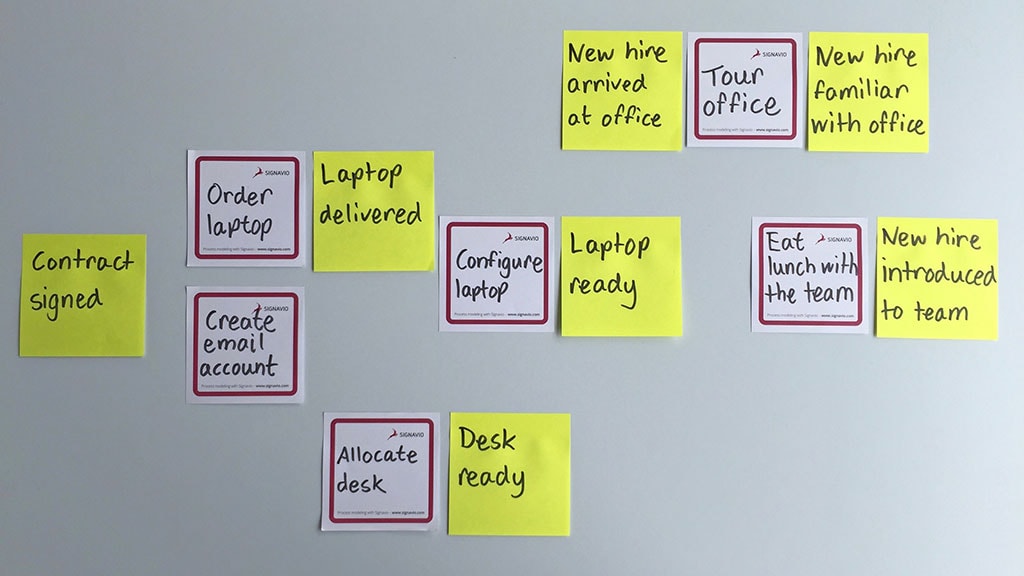

To add events to the tasks timeline, write their names on different colour sticky notes to the tasks, and position them between the tasks, which you’ll have to move to make space.

At this point, you will probably want to revisit the tasks. The last tasks don’t look like the end of the onboarding process: asking ‘What’s next?’ after getting to know the team and the office will result in additional tasks, such as ‘Assign new hire to project’ or ‘Plan training.’ You may also want to split tasks into separate tasks, when an interesting event happens in between.

You might also struggle with how to represent the order of events. In this example, the new hire’s laptop and desk can be prepared in parallel, but you don’t know (or necessarily care) what happens first: ‘Desk ready’ or ‘Laptop ready’.

What you do want is for both of those events to happen before ‘New hire arrived at office’, but you probably can’t guarantee that, unless you take the unusual move of telling new hires not to turn up until their desk and laptop are ready. These issues don’t belong in this high-level model, so you are better off representing the ideal case. Similarly, you can ignore everything else that can go wrong, for now.

Adding the events exposes a limitation of the timeline representation. Events that you align vertically do not necessarily happen at the same time. Instead, you merely indicate that they both happen before whatever comes next, to the right.

Next steps in process mapping

The employee onboarding process model now address what happens in the work, and why. The next steps start with who does it.

- Process Mapping Roles - who does the work

- Process Mapping Hassle vs Value - which parts of the work are essential and eliminating waste

- Process Mapping Conclusions - lessons learned, software tools, next steps.