Process Mapping

Process mapping is a core technique in business process discovery. Learn how to map processes step by step, choose the right level of detail, and create shared understanding across teams before analysis or improvement begins.

Process mapping is a core technique in business process discovery. Learn how to map processes step by step, choose the right level of detail, and create shared understanding across teams before analysis or improvement begins.

Process mapping is a core technique within business process discovery. It helps organizations make work visible by showing how activities, roles, and decisions connect from start to finish. Before processes can be analyzed, improved, or automated, they need to be clearly understood.

Within the broader process discovery landscape, process mapping focuses on structural clarity. It captures how a process works in practice or how it is intended to work, based on shared understanding rather than execution data.

This makes process mapping a common starting point for teams that want to align on how work is done before moving into deeper analysis or change initiatives.

Process mapping is the practice of visually documenting how a process works from start to finish. It shows the sequence of activities, decision points, roles involved, and handoffs that occur as work moves through a process.

In business contexts, process mapping is used to create a shared understanding of how work is performed. A process map does not analyze performance or explain why outcomes occur. Its primary purpose is to make the structure of a process explicit, so teams can see what happens, in what order, and who is involved.

Process mapping is often confused with flowcharting. While both use visual diagrams, flowcharts typically describe simple task flows or logic, whereas process mapping focuses on business processes, including roles, responsibilities, and end-to-end scope across teams or systems.

At a higher level, business process mapping refers to applying process mapping consistently across an organization to document, align, and manage multiple processes using shared conventions and standards.

Process mapping is used when teams need a shared understanding of how work is structured. It is especially helpful when processes are unclear, inconsistently understood, or spread across multiple roles and handoffs.

By making activities and responsibilities visible, process mapping creates alignment before any analysis or change takes place.

Organizations typically use process mapping when:

Process mapping is commonly used at the start of discovery initiatives because it is accessible and collaborative. Workshops and interviews allow stakeholders to contribute their understanding of how work is done, which helps surface assumptions, gaps, and inconsistencies early.

In contrast, process mining is used when organizations want to understand how processes actually run based on system data. Rather than capturing perceived workflows, it reconstructs execution from event logs.

In practice, process mapping answers “How do we believe this process works?” while process mining answers “How does it really work in execution?” Both approaches support process discovery, but they are used at different moments and for different questions.

Process mapping creates value when it helps people understand how work actually flows and agree on where responsibilities, decisions, and handoffs sit.

The goal is not completeness, but clarity. A good process map gives teams a shared reference they can use to discuss problems, align on changes, and avoid misunderstandings.

In practice, process mapping workshops work best when they follow a clear sequence. Each step builds on the previous one, and skipping early alignment usually leads to confusion later.

Most process mapping efforts struggle because teams try to capture too much too early. They aim for perfect documentation instead of a usable map. This often results in long workshops, disengaged stakeholders, and diagrams that are never used.

A more effective approach is to start small. Choose a single process, accept that the first version will be incomplete, and treat mapping as iterative. Early maps should focus on the main flow and common scenarios, not every possible exception.

In real-life settings, teams that succeed with process mapping:

This mindset lowers the barrier to participation and helps teams build momentum. Refinement and formalization can come later, once there is shared understanding and confidence in the approach.

Every process map should exist for a reason. Without a clear purpose, teams often map processes that are either too broad or irrelevant to the problem they are trying to solve.

Start by clarifying why the process is being mapped. Common reasons include documenting current ways of working, resolving disagreements between teams, supporting improvement initiatives, or preparing for automation or system change.

Once the purpose is clear, select a process that has a clear structure. In practice, good candidates usually have:

Processes that are much larger or more complex are better approached at a higher level first. At this stage, also decide whether you are mapping the current state or a future state, and avoid mixing the two.

After selecting the process, define its scope explicitly. This means agreeing on where the process starts, where it ends, and what is intentionally excluded. Clear boundaries prevent the map from expanding endlessly and keep discussions focused.

Level of detail should always be driven by intent. High-level maps typically show main steps, key roles, and major handoffs. These maps are useful for alignment, communication, and orientation.

More detailed maps break steps into individual activities, include decision logic, and show rework or exceptions. These are used when the goal is analysis, handoff clarification, or improvement.

Teams often struggle with this choice. A practical rule is to start with less detail than you think you need. If people understand the flow and agree on it, the map is detailed enough. Additional detail can be added later where it supports a concrete question or decision.

Before drawing the flow, anchor the map by clarifying who is involved and what moves through the process. Roles may represent individuals, teams, or systems, and they provide the structure around which the flow is organized.

Common role types include requestors or customers, operational staff, reviewers or approvers, and automated system roles. Making these roles explicit often reveals ownership gaps, unclear responsibilities, or unnecessary handoffs.

Inputs and outcomes should also be clearly defined. Inputs describe what triggers the process, while outcomes signal completion. Examples include a submitted request, a created record, an approved decision, or a delivered service.

This step often surfaces disagreements between stakeholders. Resolving these differences early is one of the main benefits of process mapping, even if it slows progress initially.

With scope, roles, and structure defined, map the sequence of activities as they occur in practice. Start with the most common path through the process, then add decision points and variations where they meaningfully affect the flow.

Focus on what actually happens, not what should happen. Capture handoffs explicitly, as these are often where delays and misunderstandings occur. Avoid modeling rare edge cases in the first version, as they reduce readability and distract from the main flow.

A practical test helps here: someone unfamiliar with the process should be able to follow the map and explain it back without additional context. If that is not possible, the map is usually too complex or poorly structured.

Process mapping does not require formal notation to be effective. Many teams begin with simple conventions such as boxes for activities, diamonds for decisions, arrows for flow, and lanes for roles or teams. At this stage, consistency matters more than correctness.

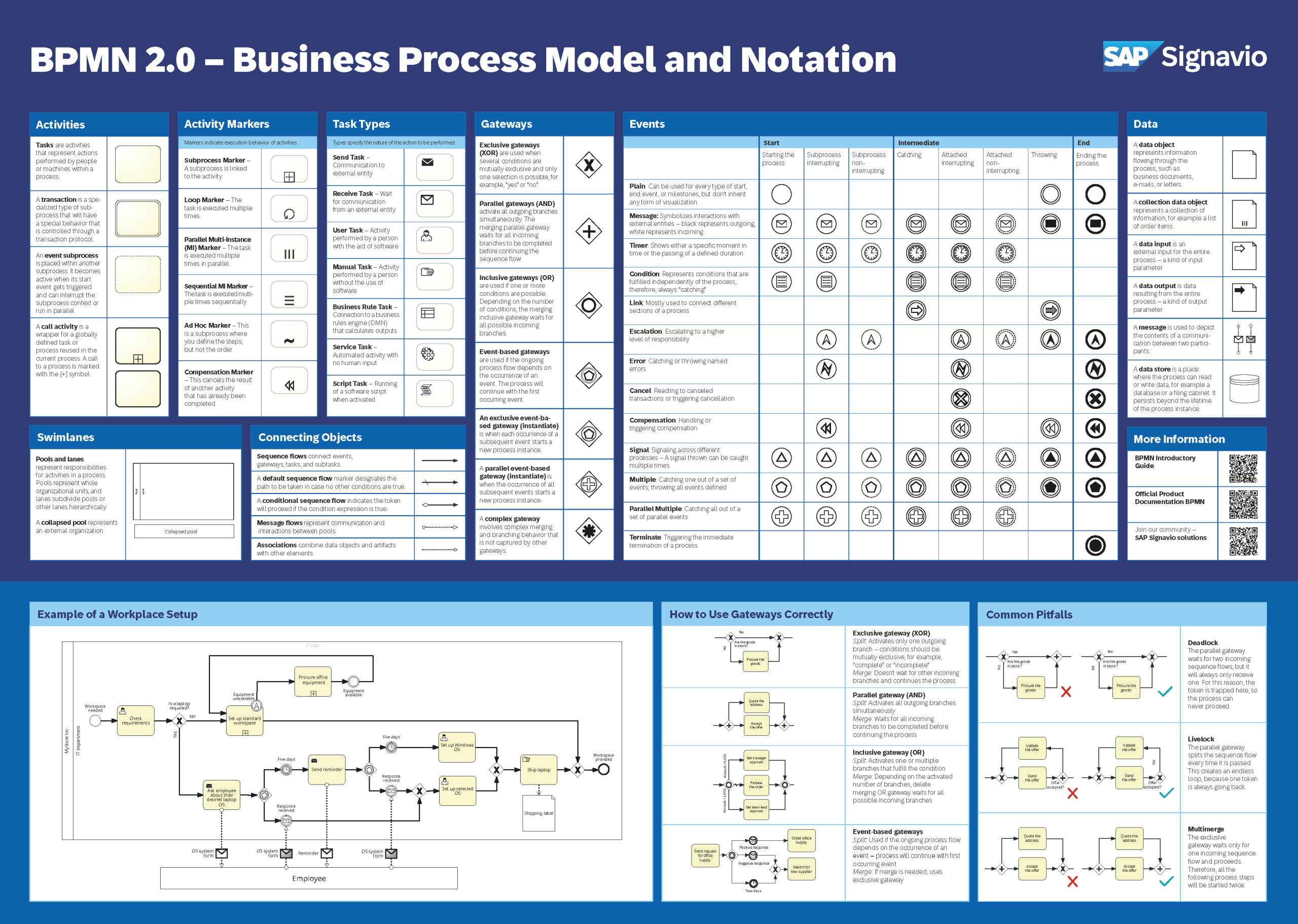

As process mapping becomes more widespread, organizations often introduce BPMN to standardize modeling, support reuse, or enable automation and analysis. This usually happens when multiple teams are mapping processes and shared standards become necessary.

In practice, beginners focus on accessibility and shared understanding, while more mature organizations focus on governance and consistency. Both approaches are valid as long as the notation supports the purpose of the map and does not become a barrier to participation.

A process map only becomes useful once it is validated by the people who work with it. Reviews typically involve those who perform the work, along with a person accountable for the process. Facilitated discussions often work better than asynchronous reviews.

Validation usually uncovers missing steps, incorrect assumptions, or unclear responsibilities. This is expected and should be treated as part of the mapping process, not a failure.

Most organizations do not aim for 100% coverage in the first iteration. Mapping around 70–80% of common scenarios is often sufficient to create value. Over time, maps are refined as understanding improves, processes change, and governance becomes more formal.

Once teams understand how to approach process mapping, the next question is how to represent processes in practice.

Different mapping techniques serve different purposes, and choosing the right one depends on scope, audience, and maturity.

A simple flow-based approach is often used at the beginning. It shows activities in sequence with basic decision points and is easy for non-experts to understand. This approach works well for documenting individual processes, aligning stakeholders, and creating an initial shared view.

Swimlane-based process mapping adds structure by separating activities by role, team, or system. This makes responsibilities and handoffs explicit and is especially useful when processes cross functional boundaries. Swimlane maps help teams see where coordination breaks down and where ownership is unclear.

End-to-end process mapping is used when the goal is to understand how work flows across multiple teams, systems, or departments. These maps typically start at a higher level and focus on major stages and handoffs rather than detailed tasks. They are often used to support alignment, transformation initiatives, or portfolio-level discussions.

In more data-driven scenarios, organizations complement process mapping with process mining. While process mapping captures how processes are understood and designed, process mining reconstructs process flows from system event data. Teams often use process mapping to align on structure and scope, then apply process mining to validate, enrich, or challenge those maps based on actual execution.

In practice, organizations rarely rely on a single technique. They combine approaches as needs evolve, starting simple and increasing structure as clarity and maturity grow.

Process mapping examples help translate concepts into practice. While every organization’s processes differ, most maps fall into a few common patterns based on scope and complexity.

A team-level process map focuses on how work flows within a single team or role. An example could be handling a customer inquiry within a support team. The map shows how a request is received, assessed, resolved, and closed, usually with a small number of steps and minimal handoffs. These maps are often used for onboarding, documentation, or clarifying responsibilities within a team.

A cross-functional process map shows how work moves between multiple roles or teams. For example, an order-to-cash process may involve sales, finance, and operations. Swimlanes are commonly used here to make handoffs visible and highlight where coordination or delays occur. These maps are useful when issues arise at boundaries rather than within a single team.

An end-to-end process map provides a high-level view across an entire business process, such as supply chain fulfillment or customer onboarding. These maps emphasize major stages and outcomes rather than detailed tasks. They are often used to align stakeholders, define ownership, and identify where deeper analysis is needed.

These examples illustrate that process maps vary in depth and purpose, but all aim to create shared understanding before analysis or change begins.

Many teams begin process mapping using documents, slides, or whiteboards. This works for small efforts, but limitations appear quickly as the number of processes, stakeholders, or revisions grows. Version control becomes difficult, maps are hard to reuse, and keeping documentation consistent turns into a manual task.

Dedicated process mapping software addresses these challenges by providing a shared environment for creating, storing, and maintaining process maps. These tools typically support role-based views, consistent notation, collaboration, and structured navigation across multiple processes. They also make it easier to reuse elements, apply standards, and link related processes together.

In practice, teams move to software when:

Process mapping tools are not about drawing better diagrams. They help organizations treat process maps as living assets that evolve over time and support broader process discovery and management efforts.

Process mapping often looks simple at first, but teams quickly encounter recurring challenges once they move beyond initial diagrams. Many of these challenges are not technical—they stem from how mapping is approached and used.

Teams try to capture every exception, variation, or system detail, which leads to complex maps that few people understand or use. A practical best practice is to map only what supports the original purpose. If a detail does not help clarify the process or inform a decision, it likely does not belong in the map.

When no one is accountable for a process, maps become outdated quickly. Assigning a clear process owner—even informally—helps keep maps relevant and prevents them from becoming static documentation.

Different teams may disagree on how work is done or who is responsible. Rather than avoiding these discussions, effective process mapping uses them as a signal that clarification is needed. Facilitated workshops often work better than asynchronous reviews for resolving these differences.

Treating maps as living artifacts, revisiting them when changes occur, and avoiding one-time mapping exercises helps ensure long-term value.

Get a BPMN 2.0 overview poster with the various graphical elements, examples of applications, and their meaning.